Next week, I need to make a decision that may strongly

impact my health a decade or two down the road. The million dollar question, "should I get back on

statins?" given that a high fat diet worked for me in the past but is a bit slow to lower my risk factor this time around. This is a long post so for the short summary, you can skip to the end (Section 4).

1. Background - 1996 to 2012

a. Experts were saying that a high fat diet would not result in weight loss, but would raise cholesterol

A

short digression will explain how I got to this point. In 1996, I

started the Atkins diet to combat my growing bulge. At the time, I was

warned not to do it because (1) Eating lots of fat can't make you lose

weight; and (2) My cholesterol would rise and I would certainly dye of a

heart attack. My doctor also cautioned me about these issues; but,

being an open-minded and intelligent individual, he suggested that my

cholesterol be monitored periodically. He also informed me that the

best medical advice of the day was that the ratio of total cholesterol to

HDL, called the risk factor, should be below 5 -- but the lower the better.

b. The experts were wrong. My weight plummeted and my health improved while I was eating lots of fat

A

couple months after I started the diet, the ratio tested at almost 8

(see green points on the plot to the right) -- so huge that I was truly

concerned. My cholesterol from a year before was inching up to 5, so 8

was a huge increase. Since my weight was literally dropping exponentially, as

you can see from the red points in the diagram to the right, I decided

to wait another 3 months (Atkins stated that the cholesterol in his

patients dropped in the long term). The reading was 6 and then three

months later, 4, and six months after that down to almost 3. So, the

critics were wrong. My weight and cholesterol remained low for over 6

years. As an added benefit, I felt great; my skin cleared to the sheen

of a baby's butt, my weekly migraines disappeared, indigestion was gone,

blood pressure plummeted, insomnia was cured, and I was full of energy. I may be confusing

correlation with causation; but, all these effects correlated with my

weight loss and risk factor decrease. The bottom line is that getting over

75% of my calories from fat and about 20% from protein did not make me unhealthy according to the metrics used by the medical profession.

c. The diet was tasty and easy to maintain for more than 6 years

The

diet was not difficult to maintain because the food was tasty and

enjoyable, and I never felt hungry. What killed my

"healthy" lifestyle was

traveling overseas. In Europe, the "healthy foods" and "exercise" did

me in. My wife and I spent a large fraction of one delightful summer in

Belgium. We had no car so we biked or walked everywhere; yet, I gained over 10 pounds. A few more years of traveling overseas and my weight

and cholesterol slowly crept up; so, I eventually took statins and

decided that my health was protected, so I went back to eating pasta,

bread, fruit, vegetables, and of course meat. By the time we got back from

our trip to Italy last summer, I was nearing my peak weight of 1996, so I

decided to once again go on the Atkins diet for good.

2. The present - Summer of 2012 to Now

I

started the Atkins diet for the second time at the end of the summer of

2012. The data appears to the left (the black points represent my

weight). Over the first two weeks of the diet, my weight hovered

between 205 and 210. Back in 1996, I had lost about 10 pounds in the

same time interval (for comparison, blue curve from my 1996 data superimposed in the

recent data.)

Internet searches revealed articles that claimed statins were responsible for all kinds of evils, from fog brain

to fatigue to increased blood sugar to muscle pain. I had experienced

all these same symptoms to varying degrees. However, these articles did

not offer proof. They were based on lots of anecdotal evidence. It is not unreasonable for people to experience all these symptoms as they age, and since statins are prescribed to older people, one could easily confuse correlation with causation.

a. Is Ezetimibe/Simvastatin the Culprit?

I

was taking Ezetimibe/Simvastatin for my cholesterol, and it did a good

job of lowering it to an acceptable level. Just as I was getting frustrated with my

lack of success on my diet, I also read articles suggesting that while

Ezetimibe/Simvastatin does indeed reduce cholesterol, some studies

showed that this particular combination (ezetimibe is a cholesterol

absorption inhibitor and simvastatin a statin that inhibits HMG-CoA) was

no better in outcome than a simple statin. And since statins alone did

not lower my cholesterol, I wondered whether I was really being

protected from heart disease.

b. Testing the hypothesis that Ezetimibe/Simvastatin interferes with weight loss

While I could not determine the efficacy of the Ezetimibe/Simvastatinin in protecting me from heart disease, I could test its effect on weight loss. On day 19, I stopped taking my medication and the weight began to consistently drop. I accept that this may have been a coincidence, but I noticed improvements in my overall well-being - again a subjective observation.

I regularly play floor hockey year round and ice hockey in the winter. Since starting my Ezetimibe/Simvastatinin prescription, I felt a general degeneration of physical stamina. After sprinting for 10 seconds, I was exhausted, and needed to rest for longer and longer periods of time between shifts. More depressing was the unpleasant exhaustion I experienced for at least 12 hours after playing. The nature of my fatigue was not the good feeling after a workout. It was a diseased feeling. Hard to explain, but I attributed it to getting older. Remember, correlation does not imply causation, so I had no reason to believe that Ezetimibe/Simvastatinin was to blame.

About two years after starting to take my medication, I had an unexpected hit of fog brain. It was very distressing and it resulted in a lasting general fuzziness of my senses. I was concerned enough to visit my doctor, who did various tests including an MRI of my head. Nothing showed up. Again, I attributed this to aging.

After I stopped taking Ezetimibe/Simvastatinin this year, my energy and stamina returned. I can now sprint in multiple bursts in a shift without fatigue and I once again feel blissful fatigue after each game, which fades after just a couple hours. The improvements are so extreme that I am certain that the effect is real. And its been this way consistently for five months. It's harder to say whether or not the termination of medication has impacted my occasional bouts of fog brain. On this front, I would say the results are inconclusive.

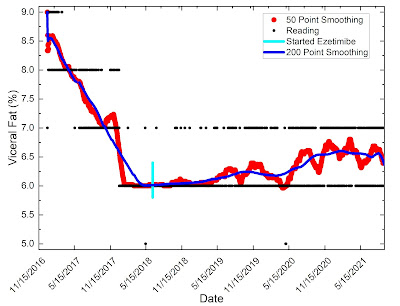

c. Effects of high fat diet on cholesterol

In my diet of 1996, my cholesterol drop lagged my weight loss by about 6 months. In reading many books on the topic, and even mentioned in Atkins book from the early 70s, the first phase of an Atkins diets is associated with a cholesterol increase due to cholesterol entering the blood stream as fat is metabolized. Once weight loss levels off, cholesterol drops. This is indeed what I observed, with more than a factor of 2 drop in my risk factor.

To track my results this time around, I am monitoring my blood (glucose, ketones, triglycerides, HDL, LDL, etc.) on a weekly basis. My experiment is complicated by the fact that I stopped taking medication during the diet and then only later started doing blood tests. In the newer figure above, the horizontal dashed red line represents my risk factor (total cholesterol/HDL) when on medication and the red points show my measurements after getting off the meds. There is a clear increase in risk factor over time, though with sawtooth features. The horizontal solid red line is the danger level, and I am in very high territory, though not as high as during the initial phase of my 1996 diet.

Because I have changed both my diet and my medications, there is no clear way to deconvolute the two. However, there is one striking feature; my weight plateaued between about day 40 and 90, followed by a precipitous increase in the rate of weight loss. In contrast, the 1996 data shows a steep and steady drop. Could the plateau be due to my metabolism making an adjustment to me stopping the medication, and I am finally in the state of rapid fat loss, thus the increase in risk factor? Did the medication change the equilibrium point of my metabolism to a more unfavorable level? Or am I just becoming old?

d. Cholesterol is not the whole story - the size of LDL particles

New research has shown that LDL comes in a distribution of sizes. The tiny particles are the ones that lodge themselves in the arteries, while the big fluffy ones do no damage. Sadly, there is no such test available in my area. However, studies show that the triglyceride/HDL ratio is a proxy for the LDL particle size and levels below 2 are good. The green squares show my data and the horizontal green line labels a ratio of 2. In this regard, my numbers during my 2012 are good.

3. The Science

The issue of diet has been highly politicized and much of the research is not science. I recommend that readers check out the books by Gary Taubs to understand how our society has become so averse to fat even in the face of contrary evidence. There have been many criticisms of his book that he selectively chooses data that supports his views and ignores the other data. To some extent this is true. However, his explanations ring true based on my experiences. The problem is that counter arguments also make sense, so how is the patient to decide the best course of action?

My intention is to study the scientific literature to develop an understanding of the ideal healthy lifestyle. Sadly, this is a daunting task given the huge number of studies. Also, given the complexity of the human body, variations between individuals, and the difficulty in doing clean studies, it is likely that no single strategy exists that applies to all individuals. If this is the case, it is foolish to come up with a one-size fits all recommendation, yet that is how patients are treated.

a. How can we judge the truth of the matter?

Here are the facts.

- Double blind studies are the hallmark of research that involves people but are not are clearly not possible to implement in diet research. My own study is not blind at all, and therefore not reliable as a test of any hypothesis, though it does confirm that increasing fat intake and decreasing carbohydrates has resulted in weight loss (1996 data and 2012 data), and based on the 1996 diet, cholesterol drops too. So, high fat diets can do some good, but are there downsides?

- Epidemiological Observational Studies (EOS) observe diets of large populations in search of correlations between diet and health (this can include whole countries or studies such as the huge one of doctors and nurses who periodically respond to questionnaires). These can be used to generate hypotheses but do not constitute proof of causation. Other studies are needed to prove anything. Unfortunately, such studies are often deemed to constitute proof. EOS studies have good statistics but do not prove anything.

- Controlled studies, in which individuals are fed strict diets under researcher supervision, or are taught to independently continue with the diet with frequent monitoring are the best comprise. The degree of intervention required necessarily limits such studies to smaller groups of individuals and therefore have sparser statistics.

- Studies on one individual, such as mine, give lots of data but suffer from bias and lack of statistics. This approach gives indicators that can be used by the individual to make medical decisions. It is satisfying when an N=1 experiment correlates with larger studies. Indeed, my weight loss dats from 1996 is much cleaner than the data in the literature analyzing the Atkins diet.

There are certain statements that can be definitively tested even in small studies. For example, the statement that people can't loose weight on low carb diets is falsified by evidence to the contrary. Controlled studies show that some people loose lots of weight on this diet. Similarly, eating lots of fat does not guarantee that you will have high cholesterol. We must also acknowledge that there are populations that eat high carbohydrate diets who are healthy, so it would be false to state that such diets always lead to poor health. However, this observation does not prove that carbohydrates make you healthy. The problem always comes down to generalizations. I need to make a decision about me, and what happens in the case of the average population is of no help.

4 What should I do?

Here is the sequence of events:

A. Historically, when I went on low fat diets (including a vegetarian diet), I

- never lost weight

- was always hungry

- suffered from idigestion

- couldn't sleep

- had chronic migraines

- felt miserable

B. On a high fat diet,

- I lost weight dramatically

- My cholesterol risk factor dropped by more than a factor of 2

- The diet was tasty, I ate as much as I wanted and was never hungry

- Many of my other indicators of health got better

- I felt great

C. I slowly drifted off of the high fat diet due to

- overseas travel were it was impossible to get enough fatty foods

- pressure to conform when dining out

- constant bombardment by the media and the medical establishment of the evils of fat

- slowly losing faith in the wisdom of staying on a low fat diet given all the persistent voices to the contrary

D. After abandoning the diet

- I tried to stay away from processed carbohydrates and eat less fatty meats

- my weight drifted upwards

- my cholesterol got high enough to require a prescription

- I was prescribed Lipator(R) but it did not lower my cholesterol

- Vytorin(R) 10/12 dramatically lowered my cholesterol

- while on Vytorin(R) for 5 years

- I became extremely fatigued after exercise

- my blood pressure increased

- I developed fog brain

- my weight increased to almost its 1996 peak

E. After going back on the diet

- My weight loss was stalled until I stopped taking Vytorin(R)

- My weight is now dropping fast

- My cholesterol levels started rising after going off the Vytorin(R)

- My fatigue after exercise is gone

- My doctor is urging me back onto statin

So, should I go back on statins? I am seeing my doctor on the 12/17/12, and will then have a blood test. I want to develop talking points with him to bring up the pertinent questions and I also want to have a decision tree ready before we talk so that I can make choices without emotion.

Here is what I am thinking:

- I do not do well when eating carbs, so my only alternative is to eat lots of fat. Since I need to continue eating fat, I need to better understand if it is having a negative affect on my health based of my higher cholesterol and C-reactive protein numbers during my recent diet. My CRP was up a few months ago, but still below the recommended value.

- If statins decrease my cholesterol and my C responsive protein (two purported risk factors for heart disease - though a causal link is not definitively established), then I would gladly take statins if they cause no other ill effects.

- Statins alone did not lower my cholesterol but the combination drug did. However, it has been shown that the outcomes (i.e. disease or death) for the combination drug is no better than for statins alone. So will a statin really help me if it does not decrease my cholesterol or CRP?

- Given that the combination drug reduces my ability to exercise, and may have other side effects, I prefer to avoid them.

- Given that statins have been shown to have positive outcomes, perhaps acting as anti-inflammatory agents, then maybe I should take them even if they do not lower cholesterol and then check my CRP and decide later if I should quit.

- What if there are other systemic effects of statins? Will they interfere with my insulin response and unravel my positive response to the high-fat diet? Could this lead to an increased chance of diabetes? Given my data, the combination drug seemed to have had an adverse effect. Are plain statins better?

- Sometimes no action is better than action if the benefits are not well defined and the risks unknown. If statins will not help with my chances of decreasing heart disease risk, perhaps I should not take them given the potential risks.

- Large scale drug tests do not take into account individual variability. What in my medical history can be used to make a more informed decision?

My plans for now are to go ahead with a blood test next week. If my numbers are getting better, I'll probably hold out for another 3 months then plan another visit to my physician. This is the simplest outcome given the fact that I expect a 6 month lag between starting the diet and stabilization of my cholesterol levels. The complication is that the combination drug may have delayed this effect. If my lipid panel is the same or getting worse, should I stay the course to give my diet a chance, or should I take the statins and risk them making me worse off in the long run by interfering with my diet?

There are clearly no clear-cut answers. What do you think?