This post focuses on the power of smoothing, which is a

process that picks out trends from noisy data. We'll see that using a low-cost bathroom scale that has a visceral fat reading, we can see an observable effect that is correlated with the start of taking Ezetimibe, a cholesterol-reducing medication.

My Yunmai bathroom scale provides a measure of visceral fat,

that greasy stuff that lines our organs.

Higher percentages of it in our body increases risks of all sorts of diseases,

so visceral fat is a good quantity to track and try to minimize. The best way to reduce its percentage is to exercise

to turn fat to muscle and to lose weight.

My scale has four electrodes, which are arranged in two

pairs. The left and right pair measure

the resistance of the soles of each foot.

The resistance from one foot to the other measures the resistance of

your body. Combined with your weight and

height, a formula is used to estimate the visceral fat.

I talked to an engineer at Cal Tech whose research was in

the general area of biometrics, and she told me that such resistance measurements

are related to the visceral fat, but they are not so accurate. Furthermore, scales such as mine are biased

towards the lower part of the body while those that use electrodes that you grasp

in your hands is biased to the upper body.

So, corrections need to be made.

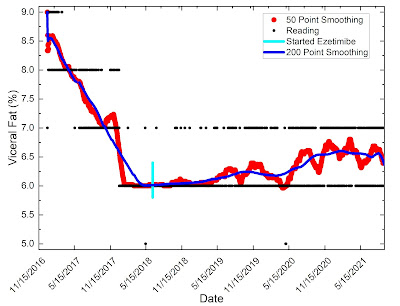

The bottom line is that I do not trust the absolute measurement but changes in the reading has some meaning provided that the scale is sensitive enough to detect the changes. In my case, my reading ranges from 5 % to 9% percent as whole numbers. The black points in the figure above show the visceral fat percentage as a function of date. These points form horizontal lines at the whole numbers and alone give us very little useful information.

However, readings fluctuate between 8% and 9% at early times

then between 7% and 8% and so on, implying that the visceral fat is falling

with time. Smoothing is the process of averaging

adjacent points. The red points show 50-point

smoothing, where 25 consecutive points to the left of the data point and 25 to

the right are averaged and plotted at the middle point of the range. As a result, we get values between the whole

numbers. Suppose that my visceral fat is

at 6.8%. Then, the scale would read 7.0%

more often that 6.0%, so the 50-point average would yield something around

6.8%. Smoothing also eliminates day

to day fluctuations that might hide the long terms trends.

The blue line shows 200-point smoothing, corresponding to over

a half-year smoothing window. This eliminates all

but the most long-term trends. The light

blue vertical line in mid-2018 shows the date on which I started to take

Ezetimibe, a medication that reduces cholesterol. In my last post, I described how I used

smoothing and a fit to a saturated exponential that found that my weight increased

by 3 pounds after I started taking Ezetimibe. The visceral fat data correlates with the observed weight gain.

To summarize the graph, smoothing shows my visceral fat

falling from late 2016 and leveling off in early 2018 while I was on my

high-fat diet. This correlates with my

weight loss. Then, after taking Ezetimibe,

my visceral fat started a long-term climb from 6% to about 6.5%. Smoothing has allowed me to determine this

rise to a precision that exceeds the whole numbers provided by the scale.

Finally, there is a dip in the 50-point smoothed curve that

falls below 6%. There is also one

reading of 5% as seen by the black point.

The date corresponds to one week after my radical prostatectomy surgery and correlates

with my initial weight loss then weight gain after the surgery.

Interestingly, the 200-point smoothed curve shows two plateaus – the

first after starting the Ezetimibe and the second one after my prostate

surgery.

As I have stressed in my past posts, this is a single experiment with potentially many confounding factors, so we cannot conclude that Ezetimibe increases visceral fat. However, the result provides a hypothesis that could be tested with a larger number of participants. Putting it all together, Ezetimibe drastically reduced my serum cholesterol (a huge effect that is consistent with controlled experiments) and is correlated with a small weight gain. This added data shows that it might add to visceral fat. This brings up the point that medications have complex effects on the body. They work as intended to treat one condition, but the side effects might oppose some of the benefits. In this case, the drop in cholesterol is far greater than the potentially ill effects of a small gain in visceral fat.

If there are others out there like me, pooling our data together could increase the confidence that the correlation is not a mere coincidence. So give it a try!